Many people are surprised to learn that single words—yes, even everyday terms—can sometimes be trademarked. But the process isn't as simple as choosing a word and claiming ownership. In trademark law, single word protection depends on factors like distinctiveness, usage, and industry context.

The common misconception is that only brand names, logos, or slogans can receive trademark protection. In reality, individual words can achieve trademark status if they meet specific legal criteria established by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and similar agencies worldwide.

This comprehensive guide explores the rules, famous examples, and legal challenges behind trademarking a single word. Whether you're an entrepreneur, business owner, or simply curious about intellectual property law, understanding these principles can help you navigate the complex world of word trademark protection. When developing your brand strategy, analyzing potential trademark words with tools like our comprehensive text analyzer can provide valuable insights into word structure and uniqueness.

Table of Contents

- What Is a Single-Word Trademark?

- Can Single Words Be Trademarked?

- Why Trademark Distinctiveness Matters for Single Words

- Famous Examples of Trademarked Words

- What Words Cannot Be Trademarked Under USPTO Rules?

- How to Apply for a Single-Word Trademark

- Common Challenges in Trademarking a Single Word

- Enforcing Your Single-Word Trademark Rights

- Global Rules on Single-Word Trademarks

- Single-Word Trademark FAQ

Comprehensive legal documentation kits help individuals and businesses understand various aspects of intellectual property and legal protection.

📋 Legal Documentation

Last Will & Testament Forms Kit (USA)

Complete DIY Legal Set • Permacharts • Professional Forms • Step-by-Step Guide

⚖️ Legal Foundation: Understanding legal documentation • DIY legal forms • Professional guidance • Comprehensive legal planning • Affordable legal resources

Build your legal knowledge foundation with comprehensive documentation resources

What Is a Single-Word Trademark?

A trademark is a distinctive sign, symbol, word, or phrase that identifies and distinguishes the source of goods or services from those of other parties. In simple terms, it's a legal tool that helps consumers recognize and associate specific products or services with particular companies or individuals.

Trademarks can take many forms: logos (like Nike's swoosh), phrases (like McDonald's "I'm Lovin' It"), sounds (like MGM's lion roar), colors (like Tiffany's distinctive blue), and yes—individual words. The primary purpose is to prevent consumer confusion and protect brand identity in the marketplace.

Unlike patents that protect inventions or copyrights that protect creative works, trademarks specifically protect commercial identifiers. They can potentially last forever, as long as they're actively used in commerce and properly maintained through periodic renewals and enforcement actions.

The legal foundation for trademarks in the United States comes from both federal law (the Lanham Act) and common law usage rights. This means you can have some trademark protection simply by using a mark in commerce, even without formal registration, though registration provides significantly stronger legal protections.

DIY stamp kits allow businesses to create custom stamps for trademark applications, business correspondence, and brand identification.

🛠️ DIY Customization

ExcelMark DIY Custom Stamp Kit

Self-Inking • Personalized Stamper • Business/Home Use • Address/Message Stamps

🎯 Brand Building Tool: Create custom stamps • DIY personalization • Business correspondence • Address stamps • Message stamps • Self-inking convenience

Create personalized stamps for your business needs and trademark documentation

Can Single Words Be Trademarked?

Yes, single words can be trademarked, but the answer comes with important qualifications. The ability to trademark a single word depends entirely on how distinctive that word is in relation to the goods or services it represents. Not all words qualify for trademark protection, and the legal requirements are quite specific.

Trademark law operates on what's called the "distinctiveness spectrum," which categorizes words into five levels: generic, descriptive, suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful. Only words that fall into the higher levels of distinctiveness—suggestive, arbitrary, or fanciful—can typically receive trademark protection without additional proof.

Trademark applications require careful legal analysis and documentation.

Generic words (like "computer" for computers) can never be trademarked. Descriptive words (like "soft" for pillows) generally cannot be trademarked unless they acquire "secondary meaning" through extensive use and consumer recognition.

Suggestive words hint at the product's qualities but require some imagination (like "Greyhound" for bus services). Arbitrary words are common words used in unrelated contexts (like "Apple" for computers). Fanciful words are made-up terms created specifically for trademark purposes (like "Kodak" or "Xerox").

The key principle is that trademark protection exists to prevent consumer confusion, not to give anyone exclusive ownership over language itself. Therefore, the same word might be trademarked by different companies in completely unrelated industries without creating any legal conflicts.

Custom wax seal stamps provide an elegant, traditional method for authenticating important documents and adding professional distinction to legal correspondence.

🏺 Premium Authentication

SWANGSA Custom Wax Seal Stamp Kit

Personalized Image/Logo • 200pcs Mixed Wax Beads • Wedding/Party/Gift Use

✨ Elegant Distinction: Custom logo/image stamps • Premium wax sealing • Document authentication • Professional elegance • Traditional craftsmanship

Add premium authenticity to your legal documents with elegant custom wax sealing

Why Trademark Distinctiveness Matters for Single Words

Distinctiveness is the cornerstone of trademark law and the primary factor determining whether a single word can receive trademark protection. A word must be distinctive enough to serve as a unique identifier for specific goods or services in the marketplace.

The legal requirement for distinctiveness serves a practical purpose: it ensures that trademarks actually help consumers identify the source of products or services. If common, descriptive words could be easily trademarked, it would create unfair monopolies over basic language and potentially harm competition.

Consider the famous example of "Apple." This word works as a trademark for computers and technology because there's no logical connection between the fruit and electronic devices. The word is arbitrary in this context, making it highly distinctive. However, no one could trademark "Apple" for actual apples or apple products because that would be generic or purely descriptive.

Distinctiveness can also be acquired over time through what trademark lawyers call "secondary meaning." Even descriptive words can gain trademark protection if they become so strongly associated with a particular source that consumers automatically think of that company when they hear the word. This process typically requires extensive advertising, widespread use, and significant time investment.

The USPTO examines distinctiveness through various factors: how the word is used in advertising, consumer surveys showing recognition, sales figures, length of exclusive use, and whether competitors use similar terms. The stronger the evidence of distinctiveness, the more likely a single word will receive trademark protection.

Visual planning tools are essential for developing trademark strategies and presenting distinctiveness concepts to clients and teams.

📊 Strategic Planning

VIZ-PRO Mobile Whiteboard (48" x 24")

Double-sided Magnetic • Portrait Orientation • Aluminum Frame • Mobile Stand

🎯 Legal Strategy Tool: Perfect for trademark brainstorming • Distinctiveness mapping • Client presentations • Team planning • Mobile convenience

Visualize your trademark strategy and enhance client presentations with professional planning tools

Famous Examples of Trademarked Words

Several well-known single words have achieved trademark protection, providing excellent examples of how distinctiveness works in practice. These cases illustrate the various paths to trademark success and the legal principles underlying word protection.

"Google" represents a fanciful trademark that was specifically created for the technology company. Originally derived from "googol" (a mathematical term), the company modified the spelling to create a unique, memorable brand name. Google's trademark protection is extremely strong because the word has no meaning outside its association with the search engine.

"Kodak" is another classic example of a fanciful trademark. George Eastman deliberately created this word because it was short, easy to pronounce, and completely meaningless—making it perfect for trademark protection. The invented nature of the word provided maximum distinctiveness from the beginning.

"Facebook" demonstrates how compound words can function as single-word trademarks. While "face" and "book" are common terms individually, their combination in the context of social networking created a distinctive identifier that qualified for trademark protection.

Successful word trademarks often become synonymous with the companies that own them.

"McDonald's" showcases how surnames can become trademarks when they achieve distinctiveness in commerce. While McDonald is a common last name, in the context of fast food restaurants, it has acquired strong secondary meaning and trademark protection.

These examples share common characteristics: they're either invented words, arbitrary applications of existing words, or terms that have developed strong secondary meaning through extensive commercial use. Each demonstrates different pathways to achieving the distinctiveness required for trademark protection.

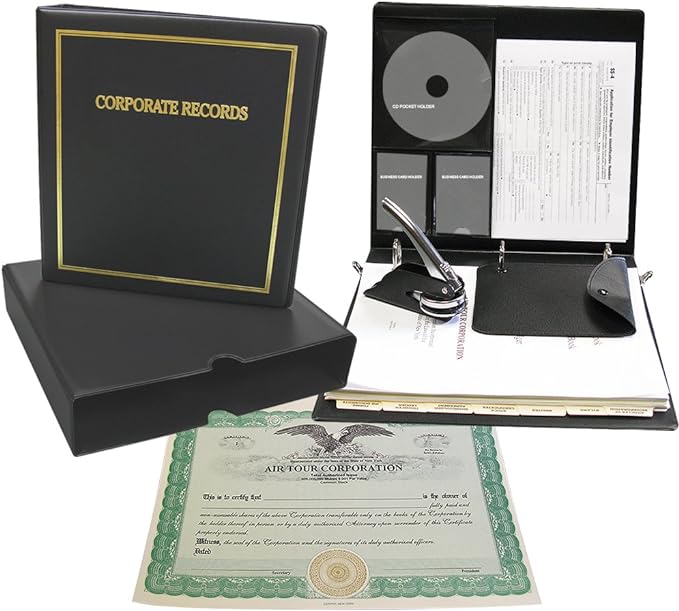

A customized corporate kit with printed documentation is essential for businesses seeking comprehensive trademark protection.

💼 Premium Corporate Setup

Corpkit Customized Corporate Kit

Printed Minutes & Bylaws • Black Binder • Slipcase • Corporate Seal • Stock Certificates

🏢 Customized Excellence: Pre-printed legal documents • Professional customization • Complete corporate setup • Trademark-ready business structure

Establish your business with premium customized corporate documentation

What Words Cannot Be Trademarked Under USPTO Rules?

Understanding what cannot be trademarked is just as important as knowing what can receive protection. Certain categories of words are automatically excluded from trademark eligibility to preserve fair competition and prevent monopolization of common language.

Generic terms are the most obvious category that cannot be trademarked. These are words that represent the common name for products or services themselves. For example, no one can trademark "car" for automobiles, "bread" for baked goods, or "software" for computer programs. Such terms must remain available for all competitors to use.

Merely descriptive words generally cannot receive trademark protection unless they acquire secondary meaning. Terms like "cold" for ice cream, "fast" for delivery services, or "bright" for light bulbs describe qualities or characteristics rather than identifying specific sources.

Geographically descriptive terms face similar restrictions. Words that describe where products come from (like "California" for wine) typically cannot be trademarked by individual companies, though geographic indications and appellations of origin operate under different legal frameworks.

Words that are too common in the industry also face rejection. If many competitors already use a term to describe their goods or services, it's unlikely to qualify for exclusive trademark protection. The USPTO examines industry usage patterns when evaluating applications.

Informational words that provide necessary information about products or services cannot typically be trademarked. Terms that consumers need to communicate basic facts about goods or services must remain in the public domain to ensure fair competition and clear communication.

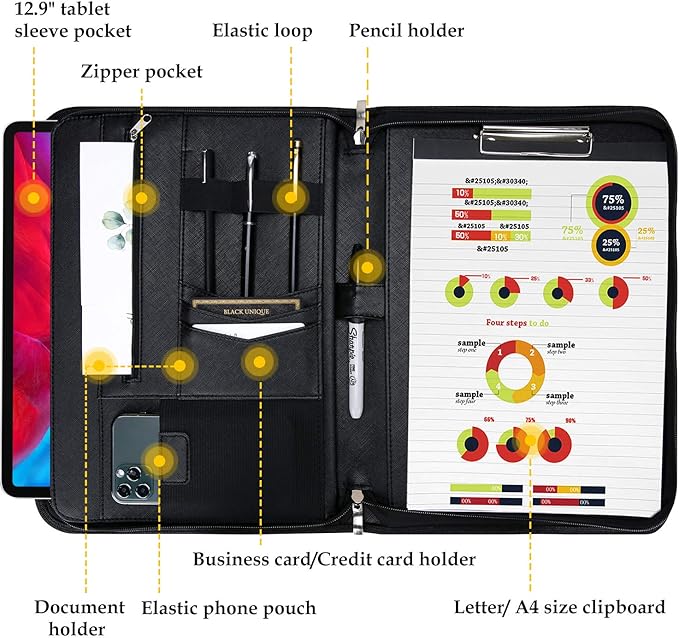

Professional portfolio organizers are essential for presenting trademark applications and maintaining organized legal documentation.

💼 Professional Presentation

ProCase Business Portfolio Padfolio

Zipper Closure • Executive Style • Letter Size A4 • Writing Pad • Document Pockets

⚖️ Legal Professional's Choice: Perfect for client meetings • Trademark presentations • Document organization • Professional image • Conference ready

Present your trademark applications professionally with organized document management

How to Apply for a Single-Word Trademark

Applying for a single-word trademark involves a systematic process through the USPTO or corresponding international agencies. The application requires careful preparation, proper documentation, and patience as the review process can take several months to over a year.

Step 1: Conduct a comprehensive trademark search. Before filing any application, search existing trademarks through the USPTO Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS), state trademark databases, and common law sources. Look for identical or similar marks in related goods and services categories. Professional trademark search services can provide more thorough analysis. Additionally, tools like our plagiarism checker can help identify if similar word combinations already exist in published content, which may indicate potential trademark conflicts.

Step 2: Determine the appropriate trademark class. The USPTO organizes goods and services into 45 different classes under the Nice Classification system. You must specify which classes your trademark will cover, and fees apply for each class. Choose carefully, as your protection will be limited to the classes you register.

Step 3: Prepare your trademark application. The application requires detailed information about the mark, how it's used in commerce, the goods or services it identifies, and when you first used it commercially. You'll need to provide specimens showing actual use of the word as a trademark. When preparing application documents, ensure precision in your descriptions using our word counter tool to meet USPTO requirements and our professional text editor for clean, properly formatted legal documents.

Custom stamps are essential tools for professional legal documentation and trademark application processes.

📋 Professional Documentation

ExcelMark Custom Self-Inking Stamp

Clear & Crisp Impressions • Personalized • Self-Inking • Small Size

⚖️ Legal Professional's Choice: Perfect for law offices • Trademark applications • Address stamps • Document authentication • Professional correspondence

Streamline your legal documentation process with professional custom stamps

Trademark applications require precise documentation and legal compliance.

Step 4: File your application and pay the required fees. USPTO filing fees range from $225 to $400 per class, depending on the application type. Electronic filing through the Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS) is recommended and typically less expensive than paper applications. Ensure your trademark applications conform to character limits by using our character counter to verify field requirements before submission.

Step 5: Respond to USPTO office actions. An examining attorney will review your application and may issue office actions requesting clarifications, amendments, or additional evidence. You typically have six months to respond to each office action, and failure to respond can result in abandonment.

Step 6: Navigate the publication and opposition period. If approved, your mark will be published in the Official Gazette for 30 days, allowing others to oppose your registration. If no opposition is filed, you'll receive your registration certificate.

Common Challenges in Trademarking a Single Word

Trademarking single words presents unique challenges that applicants should anticipate and prepare for. Understanding these potential obstacles can help you develop stronger applications and avoid common pitfalls that lead to rejection or legal disputes.

Opposition from existing trademark holders represents one of the most significant challenges. Even if your word seems available, existing trademark owners might oppose your application if they believe it could create consumer confusion or dilute their brand. Opposition proceedings can be expensive and time-consuming.

Proving distinctiveness often proves more difficult than anticipated, especially for words that might be considered descriptive or suggestive. You'll need substantial evidence showing that consumers recognize your word as identifying your specific goods or services rather than just describing general characteristics.

Geographic limitations can create unexpected complications. Even if you secure trademark protection in one country, the same word might be trademarked by different companies in other jurisdictions, limiting your ability to expand internationally without complex negotiations or legal challenges.

Maintaining consistent use requirements can be challenging for single words. Trademarks require continuous commercial use to maintain protection, and you must use the word exactly as registered. Changes in how you display or use the word might weaken your trademark rights.

Enforcement difficulties arise because single words are more likely to be used innocently by others in non-trademark contexts. Determining when someone's use of your trademarked word constitutes infringement versus fair use requires careful legal analysis and can lead to costly enforcement actions.

Proper document organization is crucial for managing complex trademark applications and legal proceedings.

📁 Document Organization

FILE-EZ Two-Pocket Folders (25-Pack)

Gray • Textured Paper • Letter Size • Professional Quality

⚖️ Legal Organization: Perfect for trademark files • Application documents • USPTO correspondence • Evidence organization • $1.08 per folder

Keep your trademark application process organized with professional filing system

Enforcing Your Single-Word Trademark Rights

Successfully registering a single-word trademark is only the beginning—you must actively enforce your rights to maintain protection and prevent unauthorized use by competitors. Trademark rights can be weakened or lost entirely through inadequate enforcement efforts.

Monitoring for infringement requires ongoing vigilance across multiple channels. Set up Google alerts for your trademarked word, regularly search trademark databases for new applications, monitor social media platforms, and consider professional trademark watching services for comprehensive coverage.

Cease and desist letters often represent the first line of enforcement action. When you discover unauthorized use, a well-crafted legal letter can resolve many disputes quickly and cost-effectively. The letter should clearly identify your trademark rights, specify the infringing conduct, and demand cessation of the unauthorized use. When drafting legal correspondence, ensure proper formatting and consistency using our case converter to maintain professional presentation standards.

Opposition and cancellation proceedings provide formal mechanisms to challenge conflicting trademark applications or registrations. These administrative procedures through the USPTO's Trademark Trial and Appeal Board can be less expensive than federal court litigation while still providing effective protection.

Federal court litigation becomes necessary for serious infringement cases that cannot be resolved through alternative means. Court proceedings can result in monetary damages, injunctive relief, and attorney's fees in exceptional cases, but litigation is expensive and time-consuming.

Remember that trademark rights exist on a "use it or lose it" basis. Failure to enforce your rights against clear infringement can weaken your trademark and potentially lead to claims that you've abandoned your rights or that your mark has become generic.

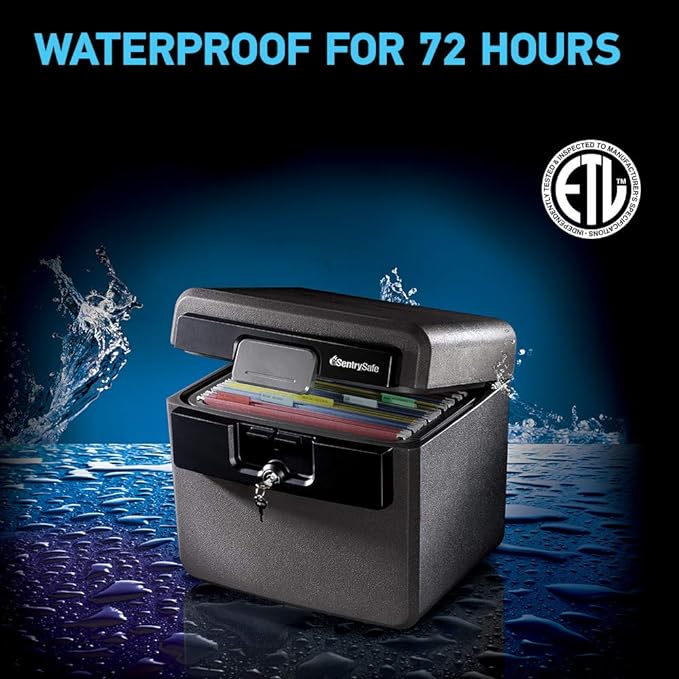

Protecting valuable trademark documents requires secure, fireproof storage to prevent loss of critical legal evidence.

🔒 Document Security

SentrySafe Fireproof & Waterproof Safe

14.3" x 15.5" x 13.5" • Key Lock • 0.65 Cubic Feet • UL Classified

🛡️ Maximum Protection: UL 1550°F rated • 72hr waterproof • Amazon's Choice • Built-in straps • Perfect for trademark certificates

Protect your trademark certificates and legal documents from fire and flood damage

Global Rules on Single-Word Trademarks

Trademark laws vary significantly across different countries and regions, creating a complex landscape for international word trademark protection. Understanding these differences is crucial for businesses operating globally or planning international expansion.

European Union trademark law operates through the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), which provides trademark protection across all EU member states through a single application. The EU system follows similar distinctiveness requirements but has different examination procedures and opposition processes.

United Kingdom maintains its own trademark system through the UK Intellectual Property Office, separate from EU protections since Brexit. UK trademark law shares common origins with US law but has evolved distinctive features, particularly regarding evidence requirements and registration procedures.

Canada, Australia, and New Zealand follow Commonwealth trademark traditions with systems similar to UK law but adapted for their specific legal environments. These countries generally require similar levels of distinctiveness but may have different classification systems and renewal requirements.

The Madrid Protocol provides a streamlined mechanism for seeking trademark protection in multiple countries through a single international application administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). This system can significantly reduce the cost and complexity of international trademark registration, though it doesn't eliminate the need to understand local law variations.

Developing markets often have less developed trademark systems with different enforcement mechanisms and legal standards. Countries like China, India, and Brazil have rapidly evolving intellectual property frameworks that require specialized expertise to navigate effectively.

High-speed document scanning is essential for managing international trademark applications and maintaining digital archives.

📱 Digital Documentation

ScanSnap iX2500 Document Scanner

Wireless/USB • 5" Touchscreen • 100 Page Auto Feeder • Cloud Enabled

🌍 International Ready: High-speed scanning • Cloud integration • Mac/PC compatible • Perfect for multi-country trademark filings

Digitize and organize documents for efficient international trademark management

International trademark protection requires understanding diverse legal systems worldwide.

Single-Word Trademark FAQ

Can I trademark a common word?

Common words can sometimes be trademarked if they're used in arbitrary or fanciful ways unrelated to their normal meaning. For example, "Apple" is a common word but serves as a strong trademark for computers. However, you cannot trademark common words for their ordinary meanings or in purely descriptive contexts.

How much does it cost to trademark a single word?

USPTO filing fees range from $225 to $400 per class of goods or services, depending on the application type you choose. Additional costs include attorney fees (typically $1,000-$3,000), trademark search fees ($300-$1,500), and potential response costs if you receive office actions during examination. When budgeting for trademark applications, calculate total documentation requirements using our reading time calculator to estimate attorney review time and associated costs.

Do trademarks last forever?

Trademarks can potentially last forever, unlike patents or copyrights. However, they require continuous commercial use and periodic renewal filings. In the US, you must file renewal documents between the 5th and 6th years after registration, then every 10 years thereafter, along with evidence of continued use.

Is it possible to lose a word trademark?

Yes, trademark rights can be lost through abandonment (stopping commercial use), becoming generic (like "escalator" or "zipper"), failure to renew registrations, or failure to enforce rights against infringers. Maintaining trademark protection requires ongoing vigilance and proper legal maintenance.

Can different companies trademark the same word?

Yes, the same word can be trademarked by different companies in unrelated industries without creating conflicts. Trademark protection is limited to specific goods and services categories, so "Delta" can be trademarked separately for airlines, faucets, and dental services without legal issues.

What happens if someone uses my trademarked word?

Unauthorized use of your trademarked word in commerce may constitute trademark infringement, giving you grounds for legal action. Remedies can include cease and desist demands, monetary damages, injunctive relief, and in some cases, seizure of infringing products. The strength of your case depends on factors like similarity of use, likelihood of confusion, and the strength of your trademark.

UNO represents a successful example of a short, memorable word trademark in the gaming industry - perfect for stress relief during complex legal processes.

🎮 Stress Relief & Team Building

Mattel UNO Card Game (Collectible Tin)

Amazon Exclusive • 2-10 Players • Family Fun • Travel Size • Collectible Storage

🎯 Perfect for Legal Teams: Office break activity • Client entertainment • Stress relief after long trademark meetings • Team building • Portable fun

Take a break from complex legal work with this classic trademarked game

Professional desk accessories like personalized name plates help establish credibility and brand identity in legal practice.

🏆 Professional Identity

Engraved Desk Name Plate (USA Made)

Personalized Engraving • Business Card Holder • Griffco Supply • Premium Quality

✨ Professional Branding: Made in USA • Custom engraving • Office credibility • Brand identity • Client impression • Premium materials

Establish your professional brand identity with premium personalized desk accessories

Conclusion: Navigating Single-Word Trademark Protection

Single words can indeed be trademarked, but success requires careful navigation of complex legal requirements, particularly the fundamental principle of distinctiveness. Whether through arbitrary usage, fanciful creation, or acquired secondary meaning, words must serve as unique identifiers to qualify for trademark protection.

The examples of Google, Kodak, Apple, and McDonald's demonstrate various pathways to successful word trademark registration, while the restrictions on generic and descriptive terms preserve fair competition and common language use. Understanding these principles is crucial for anyone considering word trademark protection.

The application process demands thorough preparation, from comprehensive searches through careful documentation and strategic classification choices. Common challenges including opposition proceedings, distinctiveness proof, and international variations require professional expertise to navigate effectively.

Remember that trademark registration is just the beginning—ongoing enforcement, monitoring, and proper maintenance are essential to preserve your rights. Single-word trademarks can provide powerful brand protection, but they require careful planning, legal expertise, and long-term commitment to maintain their value.

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about trademark law and should not be considered legal advice. Trademark law is complex and varies by jurisdiction. Consult with qualified intellectual property attorneys for specific legal guidance regarding your trademark needs and applications.

Need Help with Your Trademark Application?

Trademark law requires specialized expertise and careful attention to detail. Consider consulting with experienced intellectual property attorneys who can guide you through the complex application process and help maximize your chances of success.